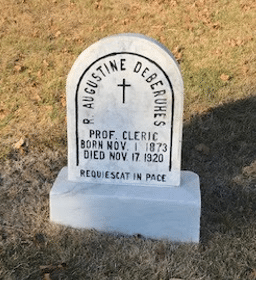

In the small cemetery just a few yards from the twin-spired church of Saint Thomas on the campus of Villanova University, a white tombstone marks the grave of novice Rudolph de Landas-Berghes.[1] Carved thereon is his name: R. Augustine De Berghes,[2] Novice Cleric, together with the date of his birth and that of his death. Nothing else distinguishes this stone from the scores of others there, each engraved with the name of a friar who had embraced and lived – some only briefly, others for many decades – Augustinian religious life. There is nothing on de Landas-Berghes’ stone that speaks to passersby of the remarkable story and the intricate journey of the man whose mortal remains have rested there for decades, a journey which was altogether unique in itself, and so unlike that of the friars with whom he is joined in death. Rudolph de Landas-Berghes had been an Augustinian novice for about eight months at the time of his death in 1920, having joined the Order at the age of 46, not quite three months after he had entered the Catholic Church.

Through “an accident of birth” [3] he entered this world in Naples, Italy, on November 1, 1873, the “accident” being that he was actually an Austrian nobleman, known properly by the name Rudolph Francis Edward St. Patrick Alphonsus Ghislain de Gramont Hamilton de Lorraine-Brabant, Prince de Landas-Berghes et de Rache, Duc de St. Winock. His father, Edward Victor Ghislain de Lorraine, Count of Landas Bourgogne de Rache was a Catholic, but for much of his life a nominal one only, and a freemason as well, but before his death in 1897 he was reconciled to the Catholic Church. His mother, Leonore Adelaide Anne de Gramont Hamilton, [4] was Anglican, and it was in his mother’s church that Rudolph de Landas-Berghes was baptized and raised.

Rudolph de Landas-Berghes succeeded to the Prince-Dukedom of de Berghes St. Winock after the death of his cousin and the extinction of the collateral male line in 1907. The princedom dates from 1344. Previously, members of the House of de Berghes St. Winock were kings of Brittany. Rudolph was also a grandee of Spain of the first class and a member of several orders of chivalry.[5]

At the age of sixteen and a half Rudolph entered the English army and served as a captain in the Sudan under Field Marshall Herbert Kitchener. He retired after a brief term of office and pursued several years of academic instruction – first at Cambridge University, from 1890 until 1893, where he attended theology lectures and the school for clergy, followed by further theological studies at the University of Paris until 1894. Confirmed in the conviction that he was being called to ministry, upon his return to England he was ordained sub-deacon by Bishop George Howard Wilkinson, the same clergyman who had baptized him years earlier, and who now placed him in charge of a church in his diocese of Truro. The young sub-deacon served there for eighteen months, waiting to reach the age when he could be ordained to the diaconate. However, during this interval he gradually became disturbed by what he judged to be a lack of authority in the Church of England, as well as by doubts concerning the validity of Anglican Orders. Following a period of discernment, after which he decided to leave Anglicanism and to enter the Old Roman Catholic Church, he traveled to Holland. There Bishop Casparus Joannes Rinkel baptized him conditionally in the Cathedral Parish of St. Gertrude in Utrecht on April 4, 1896.

The new convert made his way to the University of Brussels where he studied Literature and Philosophy for one year, and then returned to Paris to pursue Law. Within a short time, he had rejoined the English army and took part in the Nile expedition. Afterwards he was sent to South Africa. He left the army in 1904 with the rank of Lt. Colonel, and for the next three years studied privately, arriving, in due course, at the decision to convert to Roman Catholicism and enter the Norbertines in Tongerloo, Belgium.[6] In the end, however, he had a change of heart, occasioned he says, “by the appearance just then of a Papal Decree of the late Pope (Pius X)”,[7] and decided to remain affiliated with the Old Roman Catholic Church in Holland. He was re-confirmed conditionally by Bishop Van Thiel of Haarlem at St. Gertrude’s, Utrecht, on September 20, 1907, and the following year, on November 4, 1908, he received Tonsure and Minor Orders of the Old Roman Catholic Church from Bishop Arnold Harris Mathew in his private chapel in London. He was ordained sub-deacon there, conditionally, on November 16, 1909, and deacon shortly after. Finally, on November 21, 1910, Bishop Mathew ordained him to the priesthood. [8]

Arnold Harris Mathew was the first Old Roman Catholic bishop in Great Britain. A convert from Anglicanism to the Roman Catholic Church, he was ordained a Catholic priest in 1877, but following several assignments, he left the Catholic Church, and after a brief association with Unitarianism, made contact with Bishop Eduard Herzog, himself a former Catholic priest, who eventually became the first Old Roman Catholic bishop of Switzerland. Mathew had become associated with a group of Anglicans who had grown doubtful with regard to the validity of Anglican Orders and were looking for a way to bring greater credibility to the question of apostolic succession in England without having to embrace Roman Catholicism. Mathew believed that the establishment of the Old Roman Catholic Church in Britain could be the answer. On April 28, 1908, he was consecrated by Geraldus Gul, the Old Roman Catholic Archbishop of Utrecht, assisted by all the continental Old Catholic bishops, in the same Cathedral of Saint Gertrude where de Landas-Berghes had been received into the same Church twelve years earlier. Mathew then set about establishing Old Roman Catholicism in England and was elected Archbishop and Metropolitan of Great Britain. He held cordial relations with the Patriarchal See of Antioch whose Archbishop received the Old Roman Catholics under Bishop Mathew into communion with the Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch.

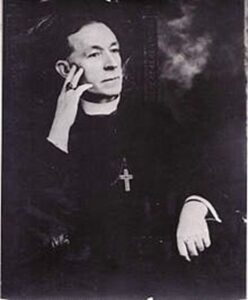

Following his ordination to the priesthood, Father de Landas-Berghes was given charge of an Old Roman Catholic church in the West End of London. On June 29, 1913 he was consecrated a bishop of that Church for Scotland by Bishops Arnold Mathew and Francis Herbert Bacon. The outbreak of World War I soon after, however, placed de Landas-Berghes in an awkward position. As a subject of the Austro-Hungarian Empire residing in Great Britain, he was susceptible to imprisonment as an enemy alien. Incarceration would have proven a great humiliation not only to de Landas-Berghes personally but also to the many royal houses of Europe to which he was connected. To avoid such an indignity, and in recognition of his service in the British army, the British Foreign Office arranged for him to go to the United States. He arrived on November 7, 1914 in New York where, with letters of introduction from the Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury, he was cordially received by the Protestant Episcopal Bishop, David Greer, whose guest in that diocese he remained for more than a year.

Though forced by the circumstances of the time to leave his diocese, of which he remained bishop nonetheless, de Landas-Berghes interpreted his move to the United States as providential. It would enable him to accomplish a goal which he had long entertained.

“I came mainly with the intention of promoting the sacred cause of the union of Christendom. The Archbishop of Canterbury suggested that the United States might afford me an opportunity of realizing my long-cherished dreams of such union, namely, that the Old Roman Catholic and Anglican Churches might become the true “via media” between the West and the East and the great Protestant bodies.” [9]

On Tuesday, January 12, 1915, shortly after his arrival in New York, Bishop de Landas-Berghes took part with 13 Episcopalian Bishops at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, New York, in the consecration of Bishop Hiram Richard Hulse as missionary bishop in Cuba. He had done so at the invitation of his host, Bishop Greer. The Reverend W. E. Bentley, an Episcopalian minister, later commented positively on this historic incident, when he wrote,

“the participation of Bishop de Landas in this event was of more than usual interest and importance, for it was the first time since the Reformation that a Bishop who is in communion with the Holy Eastern Orthodox Church and whose Orders are derived directly from Rome has taken part in an Anglican Consecration.”[10]

Nevertheless, it was a decision that de Landas-Berghes himself later came to regret.

“I may now look back on this act of participation in that service as rather injudicious, but it was really entirely in the sacred cause of Union. Except my participation in this function, I never administered Sacraments in the Anglican Church, although I have preached frequently in their principal churches both in England and in the United States.” [11]

Bishop de Landas-Berghes found the situation of the Old Catholic churches in America in great disarray. He set about the work of uniting them all into a single, strong entity. The cost of doing so proved to be painful and wearing. Nonetheless, he persevered in his goal of unification and, in 1916 was elected Archbishop and Metropolitan of the Old Roman Catholic Church in America. The Church at this period comprised a few thousand faithful and a dozen priests throughout the country, the smallest Old Catholic body in the world at the time. As Archbishop he visited the churches under his jurisdiction, “having constantly in mind the hope of one day joining the Catholic Church and possibly leading back many of those in my charge who had been formerly members of that Church.” [12] In practice, however, some of the decisions he made seem to have resulted in greater fragmentation rather than union.

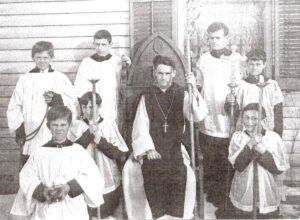

In the Spring of 1916, at the request of the European Old Catholic Bishops, Bishop de Landas-Berghes took up residence with the Old Catholic community of St. Dunstan’s Abbey in Waukegan, Illinois, and there, with the authorization of Archbishop Mathew of England, consecrated the Benedictine Abbot, William Henry Francis Brothers, to the episcopate on October 3, 1916 in the community church with a large congregation in attendance.

The following day, October 4, he consecrated Carmel Henry Carfora, a former Capuchin, who had broken with the Roman Catholic Church over a dispute with his superiors. Carfora had been ministering to Italian immigrants in New York City, Ohio and West Virginia, and was in charge of a rather extensive collection of churches and missions. In May 1907, he had founded St. Rocco’s Independent National Catholic Church in Youngstown, Ohio, after breaking with St. Anthony of Padua Catholic Church there. St. Rocco’s later became affiliated with the Episcopal Church and from 1918 to 1953 its’ pastor was a former Italian Augustinian, Oreste (Cherubino) Salcini, – now a convert to Episcopalianism – who had labored years previously for a brief time in the Order’s Italian Mission in Philadelphia.

In 1917, Bishop de Landas-Berghes and Bishop Carfora united their efforts and formally established the North American Old Roman Catholic Church with de Landas-Berghes as Archbishop and first Metropolitan-Primate. That same year they together consecrated Stanislaus Mickiewicz, a former Polish National Catholic priest, entrusting to him coordination of parishes especially of eastern European faithful.

Respect and friendliness always characterized the relationships between the Archbishop and the clergy and faithful of other Churches, consistent with his personal ambition to promote harmony and bring about unity whenever and wherever possible. The one exception to this arose from a group known as the “Living Church” which was highly critical of the Archbishop and his initiatives, causing him great heartache and distress, and leading him eventually to question the effectiveness of his work for unity.

In 1918 Archbishop de Landas-Berghes was able to write that his Church had made extraordinary strides during the three and a half years that he had been in the United States, and numbered, in addition to himself and his two suffragan bishops, Carfora and Mickiewicz, 35 priests, 1 cleric, 25 churches, 1 seminary, 1 convent, and about 50,000 members. Among these, priests, faithful, and churches were Lithuanians, Italians, Poles and Greek Rite Ruthenians. [13]

Not long afterwards, however, the Archbishop made a significant change of direction in his life – not altogether unexpected and radical considering the stated goal he had in mind at his arrival in the United States, nor in light of the difficulties he experienced in attempting to be an agent of unity. Some of his decisions regarding the bishops he consecrated were severely criticized, and as he himself saw the direction some of these bishops began to take, he might have come to question his own good judgment in their regard, or even the possibility of ever seeing the reunion of churches according to the path he was then following. At the time he was serving as professor at the Old Roman Catholic Church’s seminary which he himself had founded, attached to their Lithuanian parish in Lawrence, Massachusetts. Here he taught Greek, Latin, English, Moral and Dogmatic Theology, and Church History, using Catholic textbooks and following Catholic rituals. We might wonder if it was here in Lawrence that the Archbishop first became acquainted with the Augustinians, whose presence in the city was numerically significant.

On April 5, 1918, he wrote a fourteen-page letter, in long hand, to James Cardinal Gibbons of Baltimore, detailing his spiritual itinerary thus far and asking to be received into the Catholic Church. The letter begins, “After years of spiritual and intellectual conflicts I have at last irrevocably decided to submit to the Centre of Unity – our Holy Father the Pope, for I now clearly realize that all my studies – biblical, philosophical etc, have only brought me up against a ‘dead wall’ as it were without the living voice of infallible interpretation.” [14] He asks the Cardinal’s advice and assistance in the manner of proceeding toward acceptance into the Church, and himself suggests several possible scenarios by which he might be of service, offering to take charge of “a big slum church in a large city with hard work and small remuneration – one unsought and unpopular generally, but where I might reach abandoned souls …” (emphases original). [15]

Faithful to his constant desire to be an agent of unity, the Archbishop indicated, perhaps with overly hopeful aspiration, that his personal decision to embrace the Catholic faith would be a stimulus for others, “Many of these priests and people – and the 2 bishops – will follow my example and submit to the Church, for many of them will be simply returning to the bosom of the mother whom they have abandoned; if any, however, should feel at first indisposed to do so, as some of the Lithuanian National Church and their Bishop may be … I shall bring sufficient pressure to bear upon their leaders that they will have to compulsorily ‘capitulate'”. [16] In point of fact, the Archbishop’s decision to embrace Catholicism had no demonstrable influence on any of his bishops, priests or faithful to follow suit!

On April 22nd he again wrote to Cardinal Gibbons’ office to inform him that he was now in Fall River, Massachusetts, visiting several Polish parishes there and in Central Falls, which were under his jurisdiction. His intent, it seems, was principally to let the Cardinal know where he might be reached. [17]

Two days later he wrote yet a third time, acknowledging receipt of the Cardinal’s response to his original inquiry. The advice of the Cardinal had been clear and succinct, “… I beg to inform you that cases such as yours must be submitted direct to the Holy Office by the person interested; I would therefore suggest that you write out a clear statement of your case and send it direct to His Eminence, Cardinal Merry del Val, Secretary of the Holy Office, accompanying it with such documentary proofs as may be required.” [18] The Archbishop was very disappointed with this counsel, for the word had been circulating among Old Roman Catholics that the Secretary of the Holy Office was not at all favorable toward Old Catholics regarding collective or individual union with the Roman Catholic Church. The Archbishop had hoped, for this reason that Cardinal Gibbons himself, whom he regarded as having a “well known reputation for breadth of vision and ability to cope with the most difficult problems” would have acted on his behalf. Nevertheless, he prayed for God’s Spirit to lead him in the right direction. He also enclosed a newspaper clipping with his photo “to enable your Eminence to see what I am like.” [19]

Notwithstanding his disappointment at Cardinal Gibbon’s instructions, the Archbishop wrote to Cardinal Merry del Val without delay and pledged his “absolute and unconditional submission to His Holiness.” [20] Cardinal del Val, in turn, communicated to Cardinal Gibbons the procedure by which this submission was to be made, namely through formal reception into the Church, by the explicit and public renunciation of his errors, and a full profession of faith. The Cardinal Secretary further made clear that this would enable de Landas-Berghes to be admitted only to “lay communion”, and that the Archbishop’s orders – whether technically valid or invalid – would not be recognized by the Holy See. [21] Upon receipt of the Cardinal Secretary of State’s instructions, Cardinal Gibbons invited Archbishop de Landas-Berghes to meet him personally in Baltimore in order to share the letter’s contents with him. The meeting was set for the morning of September 5th.[22]

Archbishop de Landas-Berghes also wrote to the Prior Provincial of the Augustinian Order in the United States, Father Nicholas Vasey, reporting the steps he had taken up to that point in seeking to enter the Roman Catholic Church. [23] In his first letter to Cardinal Gibbons, he had raised the possibility of applying to the Augustinians – out of the devotion that he had toward Saint Augustine. This was an alternative to his other suggestion, already mentioned, of possibly being assigned to some large city parish, or of applying to a missionary congregation such as the Lazarists (Vincentians) which he had entertained as another option.

On July 22, 1918, Father Vasey informed the Archbishop that he would be unable to act upon his request until de Landas-Berghes had entered the Church, but that on notification of his reception his petition for admittance to the Order would be placed before the Council of the Province. As the response from Rome’s Holy Office did not come as quickly as the Archbishop had hoped, he wrote again to Father Vasey, who in mid-August could only re-iterate his earlier statement, suggesting that he follow patiently the advice of Cardinal Gibbons.

This advice was communicated in a letter which the Archbishop received from the Baltimore chancellor in December 1918, stating

“that he (Cardinal Gibbons) can only repeat what was communicated to him by the Holy Office, namely that you should retire to some Religious House or House of Retreat and there, under a competent priest, receive instruction and prepare for your reception into the Church. As you have been in correspondence with the Augustinian Fathers, His Eminence suggests that you apply to them.” [24]

Following the Cardinal’s suggestion, he wrote once again to Father Vasey. What he actually requested this time is not clear – whether a temporary stay in one of the houses of the province to receive instruction, or acceptance as a candidate for the Order – but the response of the Prior Provincial dated April 7, 1919, was unambiguous, “We could not consider your entrance into our Houses until you have been received into the Church.” [25]

The following month a now eager and increasingly impatient de Landas-Berghes appealed to the Apostolic Delegate, Archbishop Giovanni Bonzani, who answered him promptly,

“I received your letter of May 21st in due time, and immediately communicated with His Eminence, Cardinal Gibbons, concerning your case. His Eminence in answer was kind enough to send me a copy of His Eminence’s, Cardinal Merry del Val’s instructions to him regarding your submission to the Church. According to those instructions the first and essential step for you to take is to be formally received into the Church in the proper way by an explicit abjuration of error and a full profession of Faith, after which you can be absolved from censure in the ordinary way. Your orders, be they valid or invalid, will not be recognized by the Holy See, but if there be no doubt about your baptism you will be admitted immediately to lay communion. The course open to you, therefore, is to approach some one of the diocesan Bishops of this country, either directly or through an intermediary priest, and make your submission to him, and be received into the Church as a layman. You might, after you have made arrangements with the Bishop you shall have chosen, enter a House of Retreat or some Religious House in preparation for the above. As to your entrance in the Augustinian Order or any other Religious House as a member thereof, you yourself must find some Order which is willing to receive you, since the Holy See does not force any Order to receive any special candidates. The various Orders are perfectly free to accept or refuse you, just as you are entirely free to offer yourself to them or not. The same holds good in the case of being received by some Bishop for his diocese, who, even if he should accept you, would have to institute an investigation of the validity of your priestly orders and be guided by the decision of the Holy See as to your re-ordination or the acceptance of the Orders which you may already have.” [26]

In a subsequent letter, an official attached to the Apostolic Delegation suggested to the Archbishop that since he was living in New York at this time, the best thing would be for him to contact the local Catholic Ordinary, Archbishop Patrick Hayes, with regard to the matter, and that he himself would also write to Archbishop Hayes to introduce de Landas-Berghes and his situation to him. Archbishop de Landas-Berghes accordingly presented himself to Archbishop Hayes who recommended that he receive instruction from some competent priest in New York. Shortly afterwards, de Landas-Berghes called upon Augustinian Father Blaise Zeiser, pastor of the church of Saint Nicholas of Tolentine in the Bronx, whom he already knew, and was entrusted by him to the care of Father Martin Kessels, O.S.A., of the same community for instruction. Father Kessels, who had been born and raised in Holland and entered the Augustinian Order there, was familiar with the Old Catholic Church in that country.

The suggestion of this friar, then, as instructor was acceptable to Archbishop Hayes, and from November 9 until December 8 the two met every other day for four hours. [27] At the completion of the instructions, Father Kessels wrote a report with details of the Archbishop’s curriculum vitae, his religious itinerary, process of inquiry and topics covered in their classes. He concluded, attesting to the Archbishop’s sincerity and preparedness, and his recommendation that he be received into the Church. [28] On December 22, 1919, Rudolph de Landas-Berghes made his profession of faith at New York’s Saint Patrick Cathedral before Archbishop Hayes who, on the same date, provided a hand-written letter attesting to the fact.[29] One of the two witnesses to the event was Father Martin Kessels.

On the very same day, at a meeting of the Augustinian Prior Provincial and his definitory at Villanova, Pennsylvania, Rudolph de Landas-Berghes’ request for acceptance as a candidate for the Order was approved. The following day Father Kessels accompanied him to Villanova and to Corr Hall, the Augustinian formation house on the college campus. The following January 25th he was approved for entrance into the novitiate.

On March 13, 1920, Rudolph de Landas-Berghes received the white habit of a novice and began his year of probation under Father Patrick Kehoe, O.S.A. He took the name of Augustine, in honor of the saint whom he had admired for so long and under whose Rule he would now live. His long-held desire to enter religious life in the Catholic Church was realized and the first formal stage of incorporation had begun. The timing of his admittance was a bit unusual, for a group of novices were just about to end their year of training and were approaching the time of profession,[30] and another would not begin until the end of June. Nonetheless, it was not unprecedented that someone enter the novitiate in the course of the year, and perhaps de Landas-Berghes’ experience, as well as his great eagerness, allowed for an exception in his case. Thus, he lived in close association with one group of candidates for approximately four months, and with another group for six months. One of his fellow novices from this second group wrote about his former classmate many years later, in a precious document which gives some insight into the character of the former Archbishop.

“He was a quiet, silent and prayerful man … he seemed a lonely, thoughtful character who had made a great decision and was struggling to fulfill it. He spent his days in prayer and studying. It seemed that he carried on a big correspondence, as I noticed the letters in the mailbox, the wax seal calling my attention to the large, unusual envelopes. During the recreation periods of the summer months at Villanova, very often Archbishop de Berghes would spend his evenings with his fellow-novices, telling about his younger days, leaving the impression on us of great sacrifice and fortitude on his part in his seeking the true faith and the best way to serve God that now led along a road of great humility and patience. It was this virtue of humility that impressed me most deeply, a man of high position observing the minute commands of a stern novice-master … During the months of September and October the Archbishop did not seem to be in good health. He struck me as having a great fear of drafts in the chapel. I noticed his impatience at open windows and the way the cold affected him, as though he had constant chills. Eventually, he took to his bed for a few days at a time. I did not seem to be too surprised when one day in November I learned that he died rather suddenly, whether of pneumonia, cerebral hemorrhage, or heart attack …” [31]

On Wednesday evening, November 17, 1920, the novice Augustine de Landas-Berghes excused himself from the dinner table and went to his room, saying that he was not feeling well. When a short time later one of his fellow novices went to his room to bring him some tea, he was found asleep in the Lord. Father Kehoe was summoned and administered absolution. Death was determined to have occurred at about seven o’clock. Augustine de Landas-Berghes was 47 years old.

From the time that he had begun to discern a call to God’s service in the Church early in adulthood, Rudolph de Landas-Berghes was intent on pursuing the path meant for him with eagerness and sincerity. The Gospel imperative ‘that all be one’ resounded compellingly within him and became, it seems fair to say, the ‘program’ of his ministry. It was, as well, however, a deeply personal pursuit which led him step by step, painfully at times and at great personal cost, to be sure, to the Catholic Church and to religious life. In the final months of his life, he would listen each week to the words of his patron, Saint Augustine, speaking through the monastic Rule he had bequeathed to his disciples, “The main purpose for you having come together is to live harmoniously in your house, intent upon God in oneness of mind and heart.” [32] We can only imagine what those words meant for him after so long a journey.

Michael Di Gregorio, O.S.A.

Villanova, Pennsylvania

[1] I have chosen to use throughout the spelling of this abbreviated form of his name as he himself used it in signing the several extant letters referenced here.

[2] Augustine is the name he took upon entering religious life.

[3] Archives Archdiocese of Baltimore, 124E2, Letter of Archbishop de Landas-Berghes to Cardinal Gibbons, dated ‘Feast of St. Vincent Ferrer, (April 5) 1918’, from Bishop’s House, 156 Garden Street, Lawrence, Massachusetts.

[4] A note in the Augustinian Archives at Villanova puts his mother’s death in the year 1898.

[5] Augustinian Archives Villanova Province, clipping of Obituary in Philadelphia’s Catholic Standard and Times, November 23, 1920.

[6] de Landas-Berghes had been in communication with Abbot Geudens, who was then superior of the English mission of the Abbey.

[7] See above, note 2. In making the statement cited here, de Landas-Berghes does not name the decree but he does make reference to the trials and punishment incurred by “some misguided men with whom I was friendly … (and) their modernistic tendencies.”

[8] The source for this information, as for many other details throughout this article, is a private paper of Fr. Martin Kessels OSA, found in the Archives of the Villanova Province. It may have served as a report from Kessels, the friar who instructed the prospective convert, to the Archbishop of New York and/or to the Prior Provincial and his Council in their assessment of de Landas-Berghes’ application to the Order.

[9] Kessels, p. 2-3.

[10] This quotation is repeated in various short articles on Archbishop de Landas-Berghes. See, for example, http://www.rmbowman.com/catholic/Hist13h.htm

[11] Gibbons, April 5, 1918.

[12] Kessels, p. 3.

[13] Gibbons, April 5, 1918.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] AAB, 124E2, p. 15, Letter of Archbishop de Landas-Berghes to Cardinal’s office, dated April 22, 1918.

[18] AAB, 124E2, p. 19, Cardinal Gibbons to Archbishop de Landas-Berghes, dated April 19, 1918.

[19] AAB, 124E2, p. 17. These quotations and attached photo are contained in the letter to Cardinal Gibbons of April 24, 1918. There are several photographs of de Landas-Berghes in the archives of the Villanova Province.

[20] AAB, 124E2, p. 20, Cardinal Merry del Val to Cardinal Gibbons, dated August 3, 1918.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Augustinian Archives. Letter dated August 30, 1918.

[23] AAVP. There are several entries in the minutes of the Definitory meetings of the Villanova Province with regard to the Archbishop’s requests..

[24] Kessels, p. 4.

[25] Ibid. p. 5.

[26] Ibid., pp. 5-6.

[27] Ibid. p. 7.

[28] Ibid. p. 7. This document was signed by both Archbishop de Landas-Berghes and Father Kessels, and dated December 11, 1919.

[29] The letter, a copy of which is kept in the Villanova Province Archives, reads: This is to certify that Augustinus de Berghes et de Rache, a member of the Old Catholic Church with rank of Archbishop, formally abjured his error and made his profession of faith in the presence of the undersigned, and the subscribed witnesses.

[30] At the novitiate at the time were: Clement Dwyer, John Seary, John Keegan, Charles Shine, Francis Coan, Francis Masterson, Clement McHale, John Ryan. They were all professed between June 29 and July 22, 1920.

[31] AAVP. Private paper of Fr. John A. Walsh, O.S.A., May 28, 1959

[32] The Rule of Saint Augustine, 1, 3.